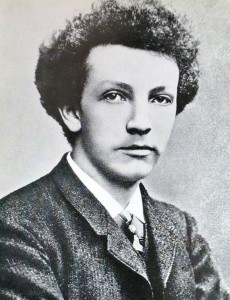

Shortly before the premiere in 1915 of his tone poem Eine Alpensinfonie (An Alpine Symphony), Richard Strauss (1869 – 1949) quipped “Now at last I have learned to orchestrate!”

He was mocked by critics for this rather smug remark; he was after all an acknowledged master and had been consulted for the update of Hector Berlioz’s seminal work Treatise on Instrumentation. And An Alpine Symphony is truly massive – it requires huge orchestral forces to perform and has a bold, passionate and meticulously written score, all carried off with Strauss’s characteristic aplomb. For many it is his crowning orchestral achievement and a summation of his virtuosic skills. It’s also a testament to his remarkable industry as he orchestrated the work in only three months.

For a work seeking to evoke nature in all its majesty, only a massive orchestra would suffice for Strauss. He specifies an ensemble of well over 120 players including a 16 piece off-stage brass band (which is heard only once!), a huge percussion section, full organ and celesta. Unusual instruments and devices feature too such as the heckelphone (a rare baritone oboe), wind and thunder machines and use of the Aerophore (“Samuel’s Aerophon”), a little-known Dutch contraption to help flautists sustain long notes, consisting of a foot pump and a rubber tube.

With these gigantic forces, it’s little wonder that work is rarely performed. Even in its day it was criticised for being somewhat old-fashioned, particularly as it was written after his shockingly modern operas Salome and Elektra. But its reputation has finally been restored, largely thanks to modern recordings which do justice to its thrilling and intricate score.

Strauss is the undoubted master of the single movement tone poem (or symphonic poem). It’s a genre that originated with Franz Liszt who had composed 12 influential symphonic poems on literary themes during his years in Weimar (1848 – 1861). The genre become instantly popular with composers as an alternative to writing symphonies. Dvořák, Smetana, Mussorgsky, Tchaikovsky and Saint-Saëns all wrote symphonic poems but those by Strauss are perhaps the most striking. In his memoirs, Strauss says “[the] basic principle of Liszt’s symphonic works, in which the poetic idea was really the formative element, became henceforward the guiding principle for my own symphonic work”.

Strauss’s tone poems show his developing confidence and technical mastery, from the rather Teutonic sounding Aus Italien (1886) through an astounding string of masterpieces including Don Juan (1888), Death and Transfiguration (1889), Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks (1895), Also sprach Zarathustra (1896), Ein Heldenleben (1898) and Symphonia Domestica (1903). An Alpine Symphony (1905) would be his last tone poem and the largest by far.

The inspiration for An Alpine Symphony dates back to an event in 1879 when the schoolboy Strauss set out with a group of friends before dawn to climb a mountain in Upper Bavaria. They reached the summit five hours later and marvelled at the views but lost their way on the way down and were caught in a fierce thunderstorm. In a letter to a friend he wrote that the next day “…I described the whole hike on the piano. Naturally huge tone paintings and smarminess à la Wagner.” Years later in 1900 he wrote in a letter to his parents that he was nurturing the idea of an alpine work “that would begin with a sunrise in Switzerland; otherwise so far only the idea (love tragedy of an artist) and a few themes exist”.

Over the years he made a number of sketches but only returned in earnest in the early months of 1911 during a hiatus while working with his long term collaborator Hugo von Hofmannsthal on the opera Die Frau ohne Schatten, gruffly telling him that working on a symphony in the interim “…gives me less pleasure than shaking maybugs off trees”. He worked intermittently on An Alpine Symphony between 1911 – 1915 in his luxurious villa in Garmisch in the Bavarian Alps, completing its orchestration in the winter months of 1914.

Strauss had great ambitions and had originally planned to write a two-part work influenced by the writings of Nietzsche who once wrote “Philosophy, as I have so far understood and lived it, means living voluntarily among ice and high mountains – seeking out everything strange and questionable in existence”.

“I shall call my alpine symphony: Der Antichrist”, Strauss declared, echoing the title of Nietzsche’s notorious work of 1895, “since it represents: moral purification through one’s own strength, liberation through work, worship of eternal, magnificent nature.”

He wisely changed his mind, scaling back any philosophical ambitions to produce a highly programmatic, single movement work which evokes his youthful hiking trip, this time to a colossal and florid musical soundtrack. The care he lavished on the score is obvious at the outset. It consists of 22 unbroken musical sections with descriptive titles which signpost each stage of the journey. With over 60 musical motifs, there is little doubt that Strauss aims to depict Nature itself rather than the solitary reflections of a lone wanderer. The writing is so evocative that some critics have dismissed the work as mere film music, one scathingly referring to it as “a day in the life of an Alp”. This is rather unfair as Strauss shows his flair and mastery for filling this huge canvas with vivid and exquisite details without resorting to cliché or losing the overall sense of drama (he had earlier boasted that he could depict a knife and fork in music, if someone paid him enough money).

Of the many homages that Strauss pays in the work, those to his close friend Mahler are perhaps the most touching. Strauss was deeply upset by Mahler’s sudden death in 1911. They formed a rather unlikely friendship; Strauss was tall, imposing, somewhat inscrutable and bluntly spoken; Mahler was short, neurotic and full of self-doubt. Strauss regarded composition as a trade like any other, Mahler saw it as a calling. When Mahler used cow-bells in his Sixth Symphony, he evoked a mood; when Strauss used them in An Alpine Symphony, he evoked … cows. Mahler even remarked to his wife Alma “Strauss and I tunnel from opposite sides of the mountain … one day we shall meet”. A highly apt description!

In writing An Alpine Symphony at the Villa Strauss in Garmisch, Strauss could hardly have forgotten his stroll with Mahler in the hills above Graz on the day of the Austrian premiere of Salome in 1906 which Strauss was to conduct in front of a distinguished audience. As the sun went down, it was Mahler who suggested they return to hotel to prepare for the performance. Strauss replied “They can’t start without me … let ’em wait!”

The notoriety of Salome of course made for good box office and it made Strauss, ever the sly businessman, rich; and he built his alpine villa in Garmisch on the proceeds. With its commanding views over the Wettersterringebirge with the Zugspitze (the highest mountain in Germany), it was Strauss’s favourite place to compose and a source of continued inspiration for An Alpine Symphony.

Strauss was quite pleased with the work, even if it created few ripples on its first performance. Writing to Hofmanstahl he said “I do hope we shall see you soon. You must hear the Alpine Symphony on Dec. 5th; it is really quite a good piece!” We can all agree with that assessment wholeheartedly; not only is it “quite a good piece” it’s a thrilling and unforgettable journey.

Kevin Painting

@berggasse

Published 23 November 2015 on primephonic