For many, the music of Ralph Vaughan Williams [1872 – 1958] evokes a dreamy, nostalgic vision of England – more Downton Abbey than Dickens – with folk music blending with tranquil, rural landscapes, and a suggestion of Choral Evensong with “hallowed traditions and hallowed halls”. And his most popular works – The Lark Ascending, Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis and Fantasia on Greensleeves – tend to cement his status as the most quintessential composer of English pastoral music.

A contemporary critic and composer, Peter Warlock, once waggishly remarked that Vaughan Williams’ music is “… too much like a cow looking over a gate”. However, a deeper familiarity with his music gives the lie to this caricature. Vaughan Williams is adept at evoking landscapes and nature: from rural idylls and bustling cityscapes, to bleak and desolate wildernesses. Far from being reassuring, his music often has the power to be deeply unsettling.

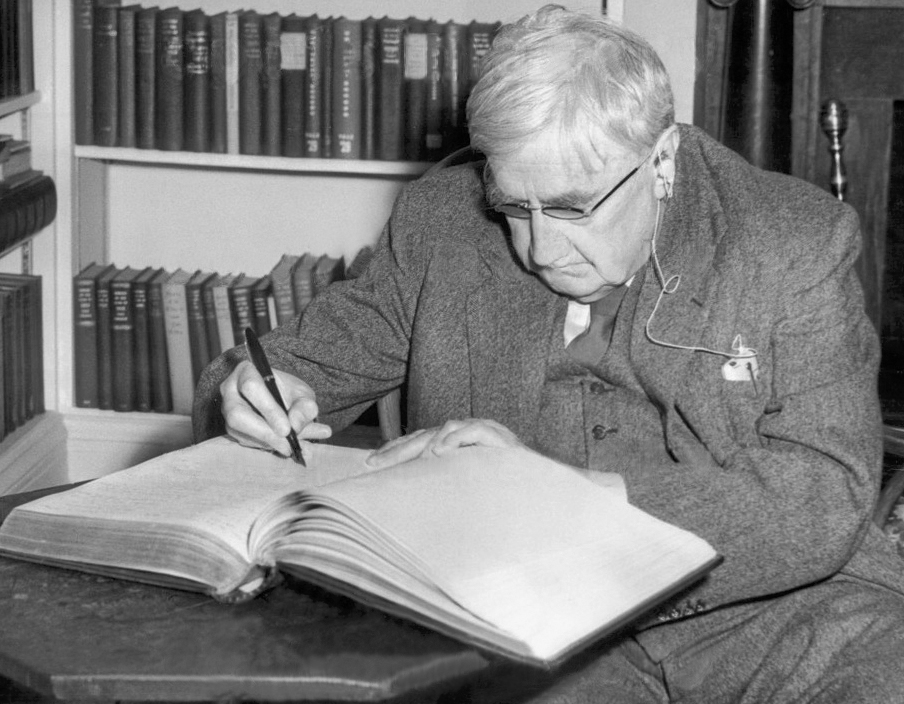

Ralph Vaughan Williams was born into a comfortably-off middle class family in the picturesque Cotswold village of Down Ampney. His mother was the great granddaughter of Josia Wedgwood and a niece of Charles Darwin; his father (a clergyman) hailed from a distinguished family of lawyers. With a generous private income, the young Vaughan Williams could afford an extended musical education at the Royal College of Music in London and at Trinity College, Cambridge. Further study followed in Berlin with Max Bruch. His collecting and cataloguing of English folk music with his lifelong friend Gustav Holst in the early 1900s was a decisive influence on his music. But it was his brief studies with Maurice Ravel in Paris when he was 35 (for what he called “a little French polish”) that gave him a renewed confidence in the development of his own distinctive voice.

Of his time in Paris, Vaughan Williams wrote in his autobiography that Ravel “…paid me the compliment of telling me that I was the only pupil who ‘n’écrit pas de ma musique’ [didn’t write my music]”. They became friends and had a mutual admiration for each other’s music. In 1912, Ravel even gave the French premiere in Paris of his song-cycle On Wenlock Edge, a performance which Vaughan Williams later recalled with some chagrin as being one of the worst that he’d heard.

In Vaughan Williams’ mature compositional style, pastoral melodies are transformed with suggestive harmonies (and vivid, sumptuous orchestral colours) to create a musical language that is entirely his own but capable of great expression – from sublime idylls such as the magnificent Serenade to Music, to the angry outpourings of his fourth and sixth symphonies.

Two works in particular demonstrate his mastery at depicting the human condition in the face of hostile, implacable nature: his opera Riders to the Sea (1927) and his seventh symphony, Sinfonia antartica (1949 – 1952).

Riders to the Sea is a faithful adaptation of the tragic, one-act play by the celebrated Irish dramatist J. M. Synge about a poor fishing community on the Aran islands, situated off the west coast of Ireland. In this doom-laden tale, the islanders’ close proximity to nature and the cruel sea emphasizes their precarious existence. The music is unsettling, menacing and struggles to find resolution. The giddying swell of the sea, with howling winds and sudden lulls, form the backdrop against which the tragedy unfolds, with wisps of musical themes being blown around like so much flotsam. Vaughan Williams however avoids using folksong. Instead, he adopts a melodic language based on the natural speech rhythms in Synge’s writing, a technique that he had used for On Wenlock Edge. He also uses wordless women’s voices for the keening (wailing) of the bereaved women.

Towards the end of the work, a submissive calm does finally descend when the central character, the old woman Maurya, resigns herself to the loss of her last remaining son. Her valediction (“They are all gone now, and there isn’t anything more the sea can do to me”) is widely regarded as the most heartfelt since Dido’s famous lament in Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas. After a brief surge from the orchestra, the music fades into silence, accompanied by an ethereal, wordless soprano voice, as if lives are slowly being extinguished by the elements.

The wilds of Ireland and Antarctica might not appear to have much in common (apart from, perhaps, beautiful scenery and terrible weather) but in his late work Sinfonia antartica, Vaughan Williams extends the musical language he’d developed in Riders to the Sea with much larger orchestral forces to depict nature, not “red in tooth and claw” but glacial, imposing and indifferent.

Sinfonia antartica has its origins in a commission to write the soundtrack to the film Scott of the Antarctic (1948). Vaughan Williams enjoyed the challenges of writing for film and the opportunities it gave for experimentation and it marked a fertile period in his creative output. Writing at the time, he said “I still believe that the film contains potentialities for the combination of all the arts such as Wagner never dreamt of”. Eleven film scores appeared between 1941 and 1958: 49th Parallel was his first, Scott of the Antarctic was his seventh and longest.

The film tells the true story of Captain Robert Scott’s ill-fated expedition of 1910 – 1912 to the South Pole. It’s a fine example of the “stiff upper-lip” British films produced by Ealing Studios and it boasts a stalwart cast (including the young actor Christopher Lee who, some 60 years later, endeared himself to a new generation of music lovers by singing heavy metal). It’s a credit to Vaughan Williams that many regard his musical score as more memorable than the film itself, but the project fired his imagination and he immediately intuited its symphonic dimensions. The resulting symphony is therefore an extensive reworking of material from the film.

Sinfonia antartica is written on a grand, expansive scale and it calls for huge orchestral forces. The colorations are striking in their originality but the symphony avoids being a meretricious display of orchestral effects. For instance, the Intermezzo is located in the familiar Vaughan Williams musical territory of a rural idyll – but it’s an unsettling one, being disturbed by disquieting harmonies and the ominous tolling of bells, suggesting an elegy for the dead.

Central to the work is the theme of human striving and heroic endeavour which forms the basis for the musical development. This is played out against a slowly moving landscape, wonderfully realised, with nature at its most beautiful, majestic and, ultimately, terrifying. The noble but doomed theme at the beginning of the work is transformed in the last movement into a weary trudge against the elements. Elsewhere, the wordless soprano and female voice choir seem to represent the sirens of Greek mythology, enticing the explorers to their doom; their “cold, chromatic wailing” also rounds off the work, accompanying the blizzard which whistles across the bleak landscape. Musically this is similar to the keening women in Riders to the Sea, but here an other-worldliness is suggested, in much the same way that Holst had used a female choir to evoke the remote outer realms of space in his orchestral tour de force, The Planets.

There is plenty to discover in Sinfonia antartica. Some commentators feel that because of its programmatic origins it is more of tone poem, a sort of musical collage. At its first performance, some even objected the use of an off-stage wind machine, saying that it was a gimmick and had no place in a symphony (whereas it perfectly complemented the female voices). But this magisterial work, composed in Vaughan Williams’ eighth decade, beguiles audiences to this day and is a lasting testament to his mastery at evoking vivid landscapes. It is a work that his mentor Ravel would no doubt have admired.

Kevin Painting

@berggasse

Published 10 April 2015 on primephonic.