When in 1917 Sergei Diaghilev was stranded in Spain with his itinerant company the Ballet Russes and in dire financial straits, he fired off a telegram to the wealthy patron of the arts Misia Sert (and friend of Coco Chanel) in Paris for assistance. The reply was curt: “GIVE IT UP SERGE”.

This was just another jolt on the rollercoaster ride that was the story of the Ballet Russes as it teetered on the edge of financial ruin throughout its dazzling 20-year history. Its phenomenal artistic success was largely thanks to the machinations of its visionary founder, the indefatigable impresario Sergei Diaghilev.

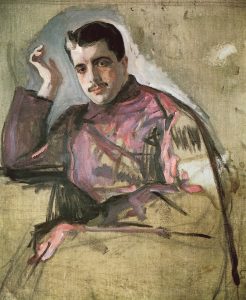

Autocratic, manipulative, charming, opportunistic and reckless, not only did Diaghilev create an environment in which the finest artists, designers and composers of the day could flourish, but he also defined an era. When he died in Venice at the luxurious Grand Hotel des Bains in 1929, he was virtually penniless and Misia Sert and Coco Chanel rushed to pay for his funeral. Without Diaghilev at the helm, the Ballet Russes soon folded and an extraordinary chapter in 20th century arts was over.

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev (1872—1929) was born into a wealthy family in Selishchi, Russia. He studied law at St Petersburg University but his early ambitions for a career as a musician were dropped after Rimsky Korsakov counselled otherwise. Smarting from this advice, he set his sights on becoming a patron of the arts; he had fallen in with a group of rising young bohemian artists and intellectuals and while they considered this self-assured, outspoken dandy their inferior, his innate sense of style, ambition, and talent for organisation was in no doubt.

He organised several successful art exhibitions and jointly founded and edited the controversial but influential arts journal Mir iskusstva (World of Art) which ran for five years. In the journal, he railed against what he saw as stagnating provincialism in the arts and he championed symbolism, art nouveau and other emerging movements.

Diaghilev came to international attention at the age of 34 in Paris where, between 1906-1908, he organised a massive exhibition of Russian art and series of concerts, including a production of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov at the Paris Opéra which brought the famous Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin to the west for the first time.

Hoping to repeat the formula in 1909 but hampered by insufficient funds, he instead brought to Paris a troupe of ballet dancers – the cream of the dancers from the St Petersburg Maryinsky theatre – for what he called a Saison d’Opera Russe, consisting of five new ballets. With exotic (and often erotic) oriental themes, unconventional choreography and the astonishing energy of the dancers, especially in the Polovtsian Dances from Borodin’s Prince Igor, the season took Paris by storm. The Ballets Russes, as they were soon called, had arrived.

Each season before the first world war brought new astonishments and scandals in equal measure; from the sexually charged Scheherazade by Rimsky-Korsakov and Stravinsky’s L’oiseau de feu (The Firebird) in 1910, the darkly erotic Prélude à l’après midi d’un faune (1912) by Debussy and most famously of all, Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) whose starkly elemental score and primitive dancing nearly provoked a riot on its first performance in 1913.

With the upheavals of war, Diaghilev abandoned the oriental exoticism of the ballets for a cleaner, contemporary avant-gard style, bringing futurism, cubism, and surrealism to the stage. He commissioned works from the Parisian group of composers Les Six among others and, for the striking design of the sets and costumes, he hired up-and-coming modernist artists, producing spectacles of ‘calculated frivolity’.

In its 20-year existence, the Ballet Russes performed around 50 new ballets and toured extensively throughout Europe, North and South America to great acclaim and launched the careers of countless artists; all of this thanks to Diaghilev’s verve, panache, and extraordinary attention to detail.

Once during a European tour, the King Alfonso of Spain asked him “Now, what do you do in the company? You don’t conduct the orchestra or play an instrument. You don’t design the mise en scene, and you don’t dance. What do you do?” Diaghilev tactfully replied “Your Majesty, I am like you. I do no work. I do nothing, but I am indispensible.”

Diaghilev’s achievements are all the more remarkable when one considers that he had no money; at least none of his own (his father was declared bankrupt in 1890). But with his commanding manner and disarming charm, he assiduously cultivated and exploited his rich and aristocratic connections (and anyone who might prove remotely useful) for supporting his new ventures. This paid off handsomely. Not only did he manage to rustle up sufficient money for his productions but his contacts were also a convenient cash cow for the perennially impecunious impresario who left debts and unpaid hotel bills in his wake.

On other occasions the connections proved useful for practical reasons; through diplomatic channels he secured the release of Nijinsky from house arrest in Budapest during the first world war (Diaghilev needed him for the 1916 season in New York).

He also understood the power of notoriety and scandal to pack the theatres, even if the intention was to provoke rather than to shock audiences. Nijinsky’s pioneering choreography and uninhibited dancing for Prélude à l’après midi d’un faune (1912) provoked a storm in the press, Le Figaro screaming ‘Un Faux Pas’, the Pittsburgh Gazette following up with ‘WICKED PARIS SHOCKED AT LAST’. Little wonder that Diaghilev was pleased with storm that greeted Le sacre du printemps in 1913 on its opening night, admitting that it was “Exactly what I wanted!”

But his real genius was his alchemic gift for bringing together such a diverse array of artists and collaborators to produce works of the highest order.

At different times, with the designers Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois and artists such as Braque, Chagall, Cocteau, de Chirico, Derain, Matisse, Picasso and Roerich, he produced arresting and visually stunning spectacles.

Debussy, de Falla, Milhaud, Poulenc, Prokofiev, Ravel, Respighi, Satie, and Stravinsky all composed music for his ballets and Stravinsky’s masterly scores for the three Russian ballets (The Firebird, Petrushka, and The Rite of Spring) are rightly considered as masterpieces of the genre.

Diaghilev also raised the status of the male dancer which had previously been rather neglected. Among the famous principal dancers were Vaslav Nijinsky, Léonide Massine, Anton Dolin, Serge Lifar (all were his lovers over the years), Michel Fokine and George Balanchine. The principal female dancers included: Anna Pavlova, Ida Rubinstein, Bronislava Nijinska, Lydia Lopokova and Alicia Markova.

Stories about the rivalries and infighting at the Ballet Russes are legion. This is depicted in the classic film The Red Shoes (1948); it also contains a thinly veiled portrait of Diaghilev in the manipulative character of Lermontov whose hectoring drives a ballerina to her tragic death. (Interestingly, the film also features Léonide Massine in a minor role as the shoemaker).

Henri Matisse perhaps best summed up the atmosphere at the Ballet Russes to his wife in a letter when he wrote “You can’t imagine what it’s like, the Ballets Russes. There’s absolutely no fooling around here – it’s an organisation where no one thinks of anything but his or her work – I’d never have guessed this is how it would be.”

Diaghilev’s famous exclamation to Jean Cocteau “Astonish me!” sounds like a rallying cry to artists everywhere. But what a hard act to follow.

Kevin Painting

@berggasse

Published 29 August 2016 on primephonic.